Baltimore, MD (August 15, 2017)

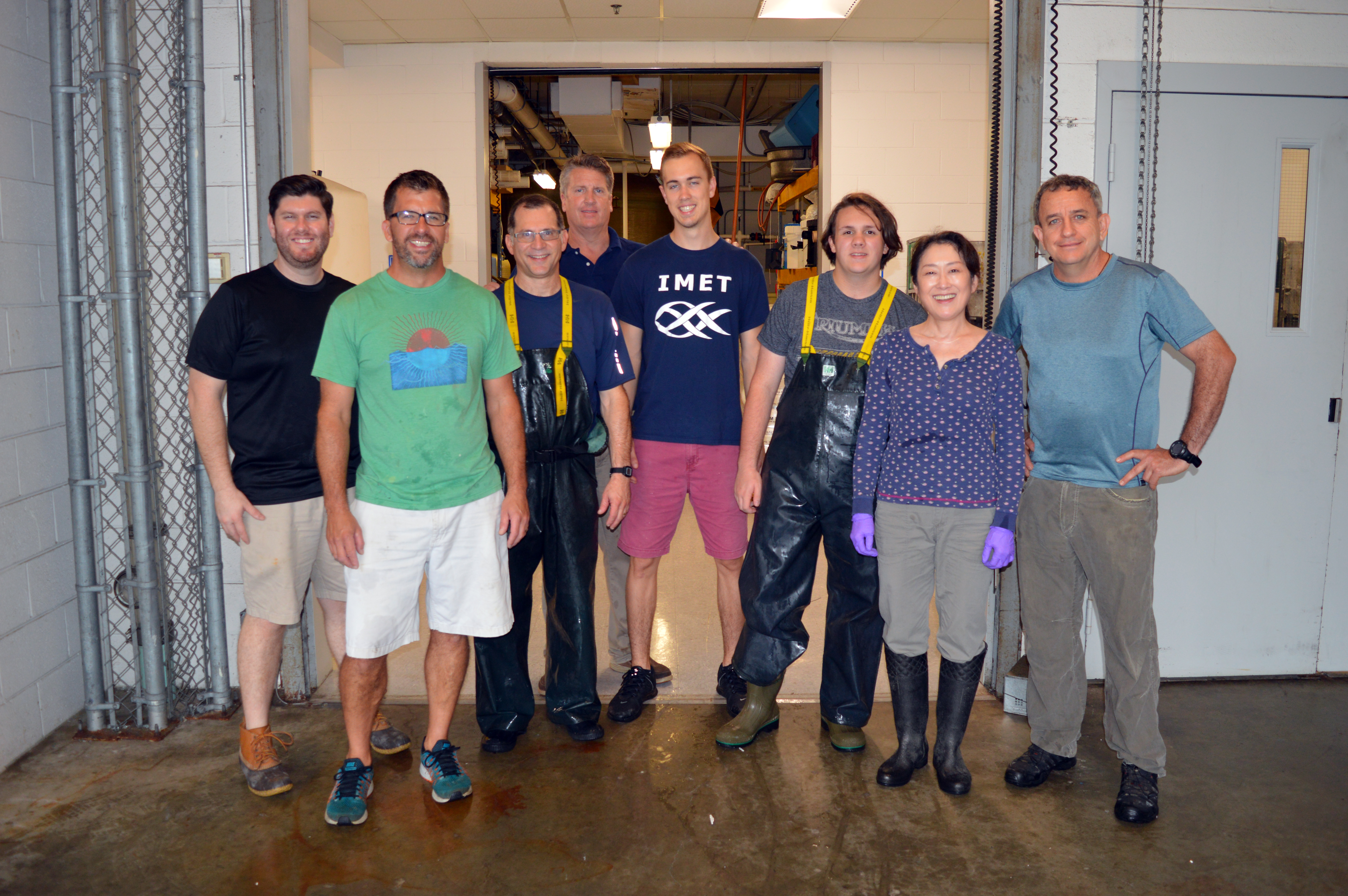

Working in assembly line fashion, a team from the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology (IMET) prepared about 15,000 European sea bass juveniles for a move north.

Great American Aquaculture (GAA), a Waterbury, Connecticut-based company, purchased the fish that IMET produced as part of an in-house breeding program, said Keiko Saito, a research assistant professor for IMET-UMBC who helped prepare the transfer.

Inside IMET is an 1,800-square-meter environmentally responsible marine facility called Aquaculture Research Center, or ARC for short. Led by Yonathan Zohar, this facility houses multiple tanks specifically designed to maintain broodstock and conduct research with fish of various species and sizes.

“Currently, we are the only aquaculture operation in North America to maintain actively spawning European seabass and to produce eggs and juveniles on demand,” Zohar said.

Pedersen called Great American Aquaculture’s work with IMET “a synergistic two-way street.” The collaboration with IMET will allow the company to begin growing seabass before its facility was ready to accept fingerlings, which is a more developed stage for the fish.

“This has a substantial economic benefit for us by shortening the amount of time required to fund our operations before we begin to generate revenues,” Pedersen said. “Dr. Zohar and his team comprise the world’s foremost authority on reproduction and the early life cycle of seabass. Having access to his experience with this species has been helpful across the board.”

European

seabass was the first marine species other than salmonid species—a

family of fishes that includes salmon and trout—to be commercially

cultured in Europe, Saito said. It is considered a high-value commercial

fish in American seafood markets and a key species for aquaculture in

the Mediterranean.

European

seabass was the first marine species other than salmonid species—a

family of fishes that includes salmon and trout—to be commercially

cultured in Europe, Saito said. It is considered a high-value commercial

fish in American seafood markets and a key species for aquaculture in

the Mediterranean.

While the fish is in demand in American markets, it is a non-native species, forcing companies like Great American Aquaculture to import it from European producers, Saito said.

“Recent development of fish farming using land-based, recirculating (closed) systems that offer superior biosecurity and full containment have opened the door for a unique and promising niche in the industry for farming of high value, non-native species,” she said.

Pedersen said shipping the fish from the Mediterranean region is expensive for the company and stressful for the fish. It takes about 30 hours from packaging at the hatchery to arrival at his Connecticut facility, he said. It took him about seven hours to drive from IMET’s loading dock.

The stress from that shipment can result in weeks of lost growth as the fish are slow to recover enough to feed.

“The shipment of fish we obtained from IMET were head and shoulders above the quality of fingerlings we have purchased from Mediterranean hatcheries. The transport went extremely smoothly and the fish have already started to feed – less than 24 hours after introduction into our system,” Pedersen said.

Part of what makes ARC unique is its recirculating operation with large-scale mechanical and biological filtration and life support systems that enable safe and efficient re-use of tank water.

Zohar

said being able to fully control the environmental conditions, such as

water temperature and salinity, expands ARC’s capabilities. Researchers

there can study and develop hatchery and other technologies for a wide

range of commercially important farmed species, such as salmon, trout,

striped bass, European seabass, Mediterranean seabream, bluefin tuna,

sablefish as well as blue crab and oysters.

Zohar

said being able to fully control the environmental conditions, such as

water temperature and salinity, expands ARC’s capabilities. Researchers

there can study and develop hatchery and other technologies for a wide

range of commercially important farmed species, such as salmon, trout,

striped bass, European seabass, Mediterranean seabream, bluefin tuna,

sablefish as well as blue crab and oysters.

ARC’s recirculating, artificial seawater is continuously treated with ozone, which maintains a disease-free environment. It’s those smaller details that make a big difference for companies like Pedersen’s.

Fish from the large commercial hatcheries abroad are not subject to the same high standards of aquaculture practiced in the United States and IMET, in particular, he said.

“In certain cases, fingerlings from abroad may arrive in the US with pathogen contamination and disease that may need to be treated,” Pedersen said. “We have a robust quarantine system in place at GAA to mitigate this risk, but the risk of diseased fish can never be completely eliminated.”