By William Blake, assistant professor, Political Science, UMBC

States can force members of the Electoral College to vote for the winner of the popular vote in their state’s presidential primary, the Supreme Court recently ruled. The July 6 decision removed one of the two reasons why the framers of the U.S. Constitution created this election system: to empower political elites who may know more about the candidates than ordinary voters. Now, the founders’ only remaining justification for the Electoral College is structural racism.

Though the Electoral College has changed since it was first used to elect George Washington to the presidency in 1789, my research shows that the system continues to give more power to states whose populations are whiter and more racially resentful.

Electoral College myths and realities

The Founding Fathers created the Electoral College in large part because they feared voters would not know all the candidates who would be running for president. In that era, most people never left their home states, so they were not likely to know candidates from other states.

The founders did not foresee the development of political parties and campaigns, which help teach voters about their options. Instead, Alexander Hamilton argued that those serving in the Electoral College would be “most likely to possess the information and discernment” needed to choose a president.

With its recent decision, the Supreme Court has abandoned the possibility that electors might vote for people other than the candidate who wins the popular vote in their state.

The other reason for the Electoral College was to bridge a major divide among the states: slavery. As James Madison said at the Constitutional Convention: “[T]he great division of interests in the U. States did not lie between the large & small States; it lay between the Northern & Southern” because of “their having or not having slaves.”

Race in early America

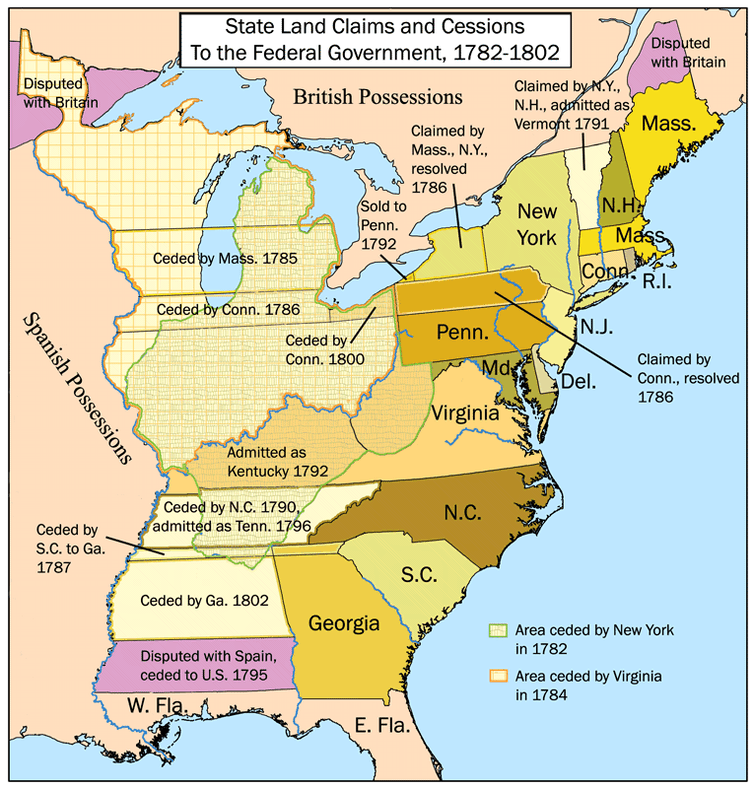

By the time the founders discussed how to pick a president, they had already made the so-called “three-fifths compromise,” counting enslaved people as three-fifths of a person in the census and allotting seats in the House of Representatives accordingly. That gave Southern slave states an advantage over the Northern states in the House.

Slave states – with many people and with fewer – insisted on the Electoral College to preserve this advantage to give them a similar advantage in presidential selection. Ultimately, delegates to the Constitutional Convention decided that each state would receive votes in the Electoral College equal to their representation in both houses of Congress.

As a result, after the 1790 census, Virginia got 21 electoral votes and Pennsylvania got 15, though both were home to just over 110,000 free white male adults, who were then the only Americans allowed to vote. That’s because Virginia had 292,627 enslaved residents, to Pennsylvania’s 3,737, the country’s very first census shows.

Similarly, South Carolina and New Hampshire had nearly identical numbers of free white men – right around 36,000. But South Carolina got two more electoral votes, for a total of eight, because more than 100,000 enslaved people lived there, compared to New Hampshire’s 158 enslaved people.

U.S. Rep. Samuel Thatcher, in 1806. Fevret de Saint Memin/Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Rep. Samuel Thatcher, in 1806. Fevret de Saint Memin/Wikimedia Commons

In 1803, the 1800 census was about to shift the balance even more toward slave states. Representative Samuel Thatcher of Massachusetts complained that counting enslaved people added significant numbers to the slave states’ delegations.

The slavery bonus ensured that the nation’s first 18 presidential elections delivered a slave-owner as either president, vice president or both. Only in 1860, with the victory of Abraham Lincoln from Illinois and his running mate, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, did a team of Northern politicians manage to beat the Electoral College’s skew toward white Southerners.

After the Civil War

Following the Civil War, the 14th Amendment removed the three-fifths clause, and the 15th Amendment should have protected African Americans’ legal right to vote. But that didn’t fix the Electoral College’s anti-Black bias. It actually made the problem worse, because Southern state governments were happy to get the representation from their large numbers of Black citizens – while keeping them from voting through discriminatory practices like literacy tests and poll taxes.

Judicial decisions at the time upheld Jim Crow restrictions on the right to vote, but those practices are illegal today.

This system benefited the Democratic Party, which was dominant in the South. Republicans tried to counter that power by strategically admitting new states from the Great Plains and Mountain West. In part because of racially disparate postwar settlement policies, these states – such as Nebraska, the Dakotas and Wyoming – were unusually thinly populated, heavily white and reliably Republican.

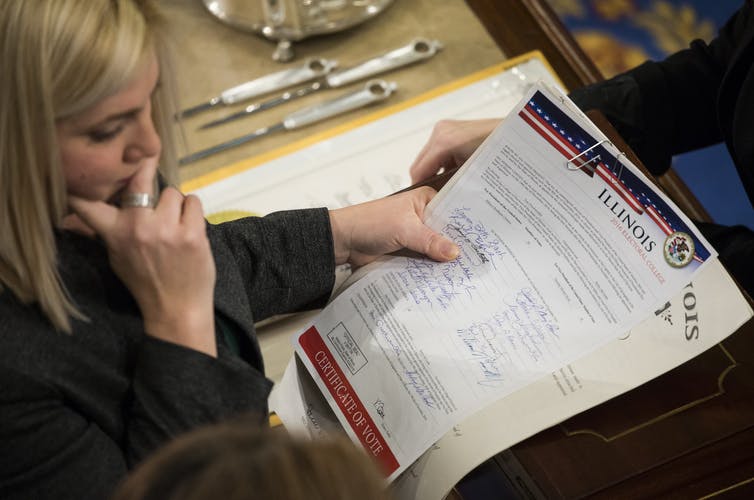

Staff of the House of Representatives review Illinois’ Electoral College vote report in January 2017. Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Staff of the House of Representatives review Illinois’ Electoral College vote report in January 2017. Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Race and the Electoral College now

Those statehood decisions made a century and a half ago still reverberate today. States with smaller populations have more electoral votes per resident because, no matter how few people they might have, they still get two senators and one House member.

I recently performed a quantitative analysis of race and the allocation of electoral votes. The data indicate that whiter states consistently wield more electoral power partly because of their population.

On average, as a state’s racial composition gets whiter, its electoral power increases. For instance, in 2016, North Dakota was the seventh whitest state and 47th on the list in terms of adult population. It had more than 5.2 electoral votes per million adult residents, when an average state had just 2.2 electoral votes per million adult residents. According to my analysis, a state that is 10% whiter than the average state tends to have one extra electoral vote per million adult residents than the average state.

I also found that states whose people exhibit more intense anti-Black attitudes, based on their answers to a series of survey questions, tend to have more electoral votes per person.

Statistically speaking, if two states’ population numbers indicate each would have 10 electoral votes, but one had substantially more racial resentment, the more intolerant state would likely have 11.

This is not an ironclad rule, and the inherent bias isn’t always decisive. For instance, Donald Trump owes his presidency to winning Wisconsin, a state that is whiter than the average state, but that has slightly less electoral votes per capita than average.

In addition, the centuries-old racial bias in the Electoral College could disappear with future population changes. Perhaps other states with relatively few people will follow the pattern of Nevada, whose population has recently become larger and more racially diverse. But the Electoral College remains a system born from white supremacy that will likely continue to operate in a racially discriminatory fashion.

*****

William Blake, Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Header image: A congressional staffer opens the boxes containing the Electoral College ballots in January 2017. Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call