When Scott Casper, dean of the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, was asked to lend his expertise in 19th-century U.S. history to help understand a unique artifact found during the Walters Art Museum renovation of the 1850s mansion at 1 West Mount Vernon Place (known to many as the Hackerman House), he was intrigued.

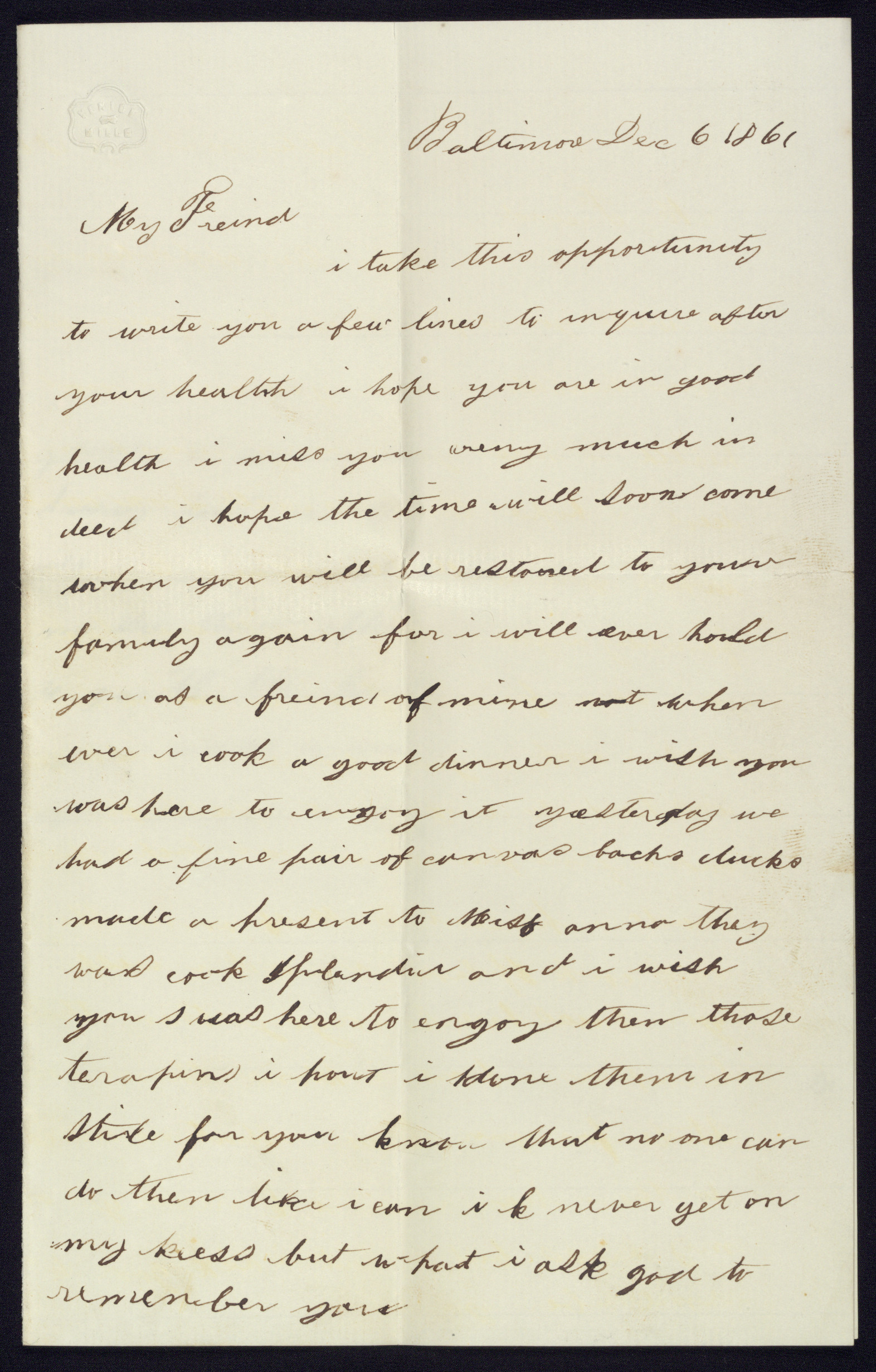

The item in question was a letter dated December 6,1861, and written by Sybby Grant, a highly skilled cook enslaved at the house, to her owner John Hanson Thomas. Casper joined the exhibition’s academic advisory committee – including experts from Morgan State University, Maryland Institute College of Art, and independent researchers – in studying the letter within the contexts of enslaved people, 19th-century Baltimore, and domestic spaces.

“We also looked at approaches to telling the stories of enslaved and employed people and how to connect particular works and artifacts in the Walters collection with the lived history of the house,” explains Casper, whose previous research includes examining the lives and experiences of enslaved African Americans in domestic settings, as well as the uses of historical evidence and memory in excavating and interpreting the lesser-known stories of historic homes.

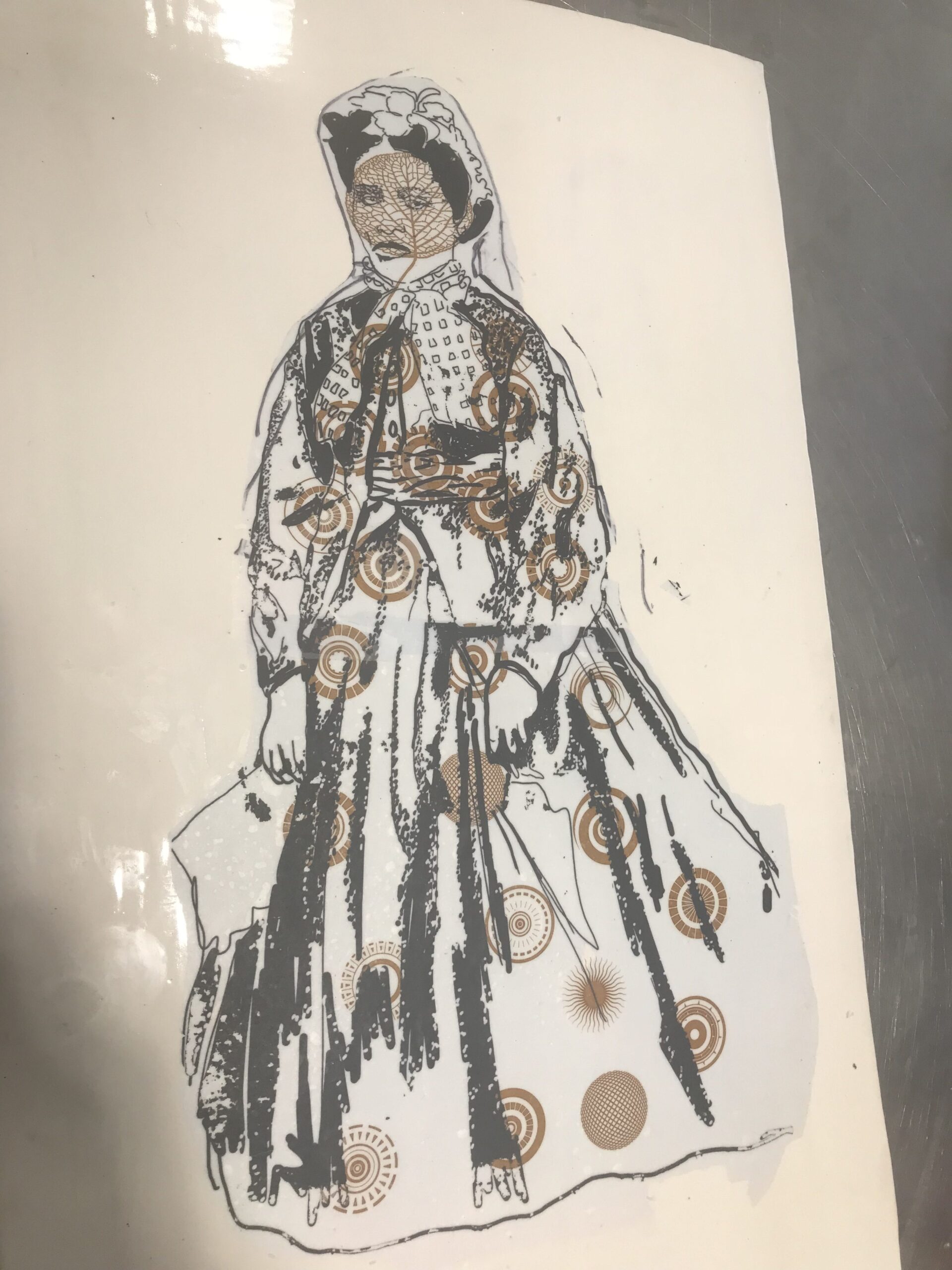

Grant’s letter paved the way for the Walters to shift the way they present not only the history of the house but also the stories that are subtly and directly represented by the art displayed at the museum. The letter is now part of a larger exhibit by ceramicist Roberto Lugo, who is known for creating fine art ceramics using traditional techniques and incorporating portraits of people of color in history to help the world remember their contribution to society and become accustomed to seeing people of color’s faces in fine art. Grant’s letter inspired Lugo to create a series of works about working women of color.

The Walters researchers once again found a partner in UMBC at the Albin O. Kuhn Library Special Collections, which houses photography, books, and archival collections, as they searched for images of freed, working class, Black women in Baltimore.

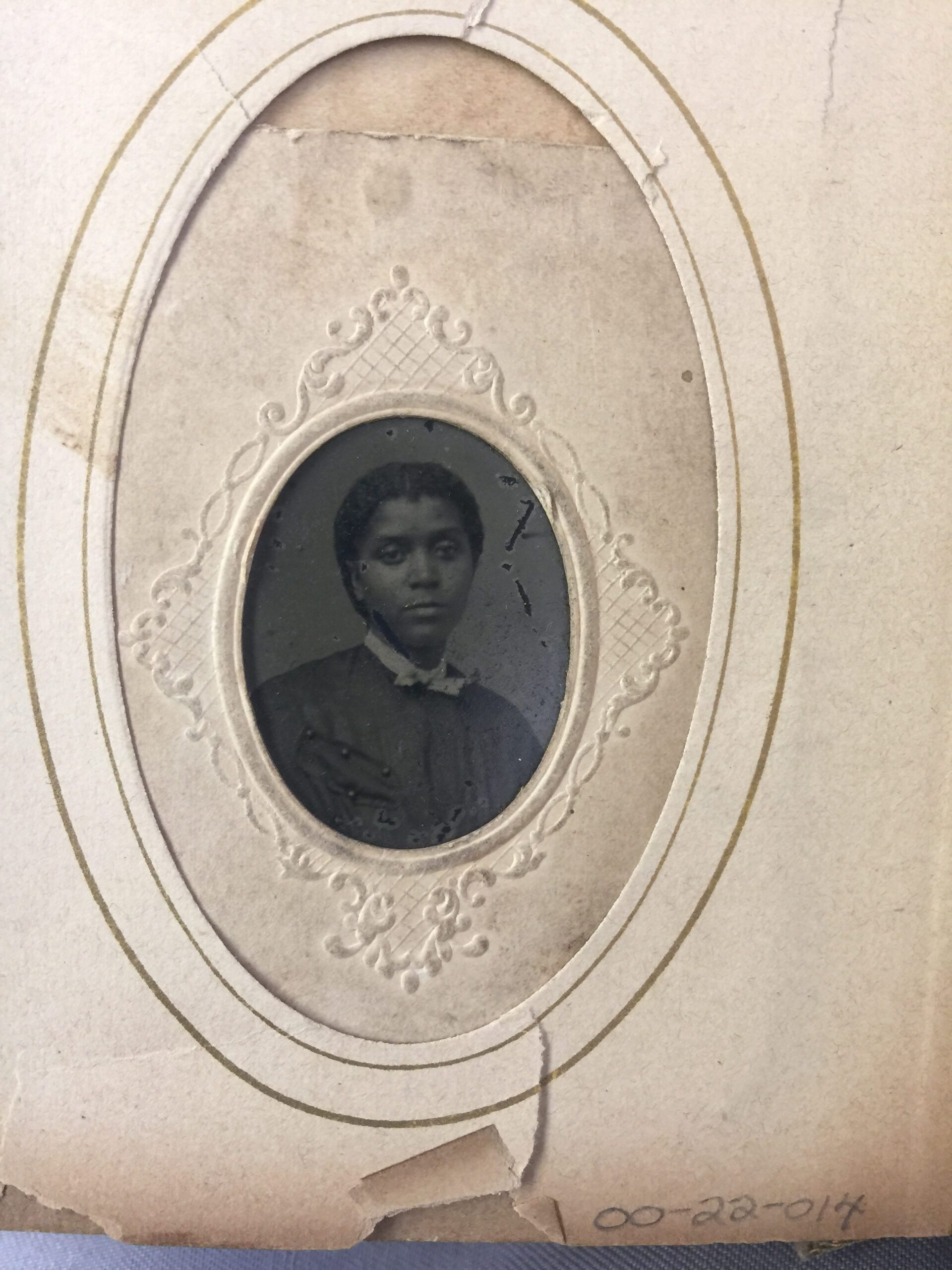

“Researchers from all over the world work with us to use digital copies of our collections,” said archivist Lindsey Loeper ’04, American studies, who helped with the request. “Our original works are also available for exhibit and have been displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. The Walters request was a challenge because in the 1800’s even working class white women were not being photographed or documented.”

The answer was found in The Baltimore African American Family Album, which contains professional portraits of African Americans from the 1860s and 1870s. The people are unidentified, and most of the photographers are also unidentified, as well. One in particular caught the eye of the Walters researchers: a portrait of a woman in a dress. The photograph inspired two fine arts ceramic tiles that now hang above the fireplace at 1 West, in what used to be the main dining room, as a tribute to Baltimore’s working women of color.

“Although I don’t know these women’s names, I know the history of my own family and they, too, are nameless, as we only have records going back a few generations, because my family used to be property,” shares Lugo. “My work in ceramics is an effort to include a community that has yet to find a place of prominence in ceramics. I’m thankful to UMBC for having such an important collection and being such an asset to our community culture and history.”

*****

Artwork by Roberto Lugo and Sybby’s letter, courtesy of the Walter’s Art Museum. Archived photography, UMBC Special Collections.