The shower was full of mantis shrimp. Bubblers burbled and the cranky crustaceans skulked in their tanks, looking for things to punch with their famously fast strikes. Complicated electronics for measuring brain activity stood sentinel beside the bed in the next room. And out on the balcony, Kathryn Feller, Ph.D. ’14, biological sciences, was wearing a respirator and gloves, working with nasty chemicals.

In other words, it was another day of fieldwork as a behavioral neuroscientist—a career Feller has embraced after a journey of self-exploration that took her to surgical operating theaters, drama summer camps, and a range of research institutions around the world. At UMBC, Feller found a robust research atmosphere, supportive lab mates, and a lifelong mentor. Now, as a professor and mentor herself, she’s able to exercise her natural creativity in a way she might never have predicted and play off her strengths from visual arts to handling sensitive scientific instruments.

Feller was in Malaga, Spain, living and working out of an attic apartment in her collaborator’s mother’s home. She was collecting data for her work at the University of Cambridge, where she was fulfilling a two-year Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Postdoctoral Fellowship focused on a new line of research into mantis shrimp vision.

Mantis shrimp are famous for two things: their powerful punches and their vision. Humans have three types of cones in our eyes for seeing color. Mantis shrimp have 16. They can see UV light and polarized light, and there is still more to learn. Feller’s Ph.D. at UMBC in Thomas Cronin’s lab focused on vision in mantis shrimp larvae. At the time there was almost no work in that area.

“While studying the visual system, a lot of times I kept wondering: ‘There’s all these cool things that mantis shrimp eyes can do, but what are they actually using this for?’” Feller says. “What are the consequences of this in a behavioral context?”

Her Ph.D. opened up the field of larval mantis shrimp vision and took her down rabbit hole after rabbit hole. “If something interests me, I follow it, and—uh-oh—here’s something else I’m interested in,” Feller jokes. In the end, her thesis explored the visual system using umpteen different scientific techniques, each providing its own insights, she says. “It was like the whole package of describing mantis shrimp

visual systems.”

Want weekly Top Stories sent to your inbox?

“Just really jazzed”

The broad scientific foundation Feller obtained at UMBC set her up well for postdoctoral experiences that have taken her around the world, including stints studying butterflies in Japan, mouse brains in Minnesota, and insects in England. In fall 2020, she launched her own laboratory as an assistant professor of biology at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

Feller’s research interests now include new projects on the connections between vision and behavior and work on brain-machine interfaces, initially inspired by a student in one of her classes. That work helped spawn a brand-new course on cyborgs that she’s teaching with Union colleagues in English and computer science.

Things are going well.

“Life is awesome. It really is. You know, it has its ups and downs; it’s not like every day is a dreamboat—I live with a two-year-old,” Feller laughs. But “at this point, I’m just really jazzed about the research I’m doing.”

(Left) Feller is the only identifiable person in the mural on the first floor of the Biological Sciences Building at UMBC. Her swim cap covered in bright plastic flowers is unmistakable. (Image; Randianne Leyshon ’09/UMBC) (Right) Kate Feller, left, teaching a new course she co-developed with English and computer science colleagues at Union College on cyborgs. (Image by Paul Buckowski/Union College)

(Left) Feller is the only identifiable person in the mural on the first floor of the Biological Sciences Building at UMBC. Her swim cap covered in bright plastic flowers is unmistakable. (Image; Randianne Leyshon ’09/UMBC) (Right) Kate Feller, left, teaching a new course she co-developed with English and computer science colleagues at Union College on cyborgs. (Image by Paul Buckowski/Union College)

Into the limelight

Back in Malaga, Feller was getting lots of great data, “but also psychologically it was a bit difficult,” she says. She didn’t speak Spanish, and her hosts barely spoke English. “For six weeks, I was just alone in someone’s house, doing science.” And then came the email: an invitation to participate in FameLab, an international competition for scientists based out of the United Kingdom. Each participant had three minutes to explain a scientific concept using only their body and any props they could carry on the stage—no slides. Entries were judged on content, clarity, and charisma.

“I got this email, and I wrote my script in one night,” Feller says. The topic? Glittery camouflage structures in the eyes of mantis shrimp larvae. “When you’re in the field, you have a finite number of hours to do what you need to do, so you need to push yourself to the extreme—but you also need to take a break. And that was my break—just to sit down and poke fun at the ridiculousness of my life.”

She won her region in the U.K. and got to spend a weekend in Devonshire, England, with the other county winners, learning about science communication and refining her talk. The final performance was at the London Museum of Science.

“I didn’t win, but it was awesome,” Feller says. After that, she was hooked on science performance. Back in Cambridge, she pursued science stand-up comedy with a group called “The Variables.”

Research requires creativity

Feller’s affinity for performance didn’t come out of nowhere. As a teenager, she attended Camp Quin, a summer arts camp in the Finger Lakes region of New York. And despite a natural affinity for visual arts, she ended up focusing on drama at the camp. A skit she developed with other campers “was hilarious, and it was a hit, and from that I was like, ‘I really like this,’” Feller remembers.

As an undergraduate at Hobart and William Smith Colleges (HWS), she participated in an improv comedy troupe and in her senior year, the Shakespeare club. In the summers, she served as a counselor at Camp Quin. Performance may have taken a backseat in her life for now, but Feller still finds that her communication skills and natural creative energy are huge benefits in her current role.

“As I’ve progressed as a scientist, I’ve learned how much imagination it takes to be a researcher,” Feller says. “And now that I’m a faculty member, I understand how much creativity you need to run an interesting class. I love that aspect—designing a new course is a super fun and creative process, and I find that my students respond quite well to the different ways of communicating I throw at them.”

Feller also applies her visual arts skills to creating research talks and class lectures. “The art of slide design is underrated,” she says. “I think that’s why I’ve been invited to give so many talks—not only do I have that performance element, but I understand the connection between hearing and seeing and information transfer.”

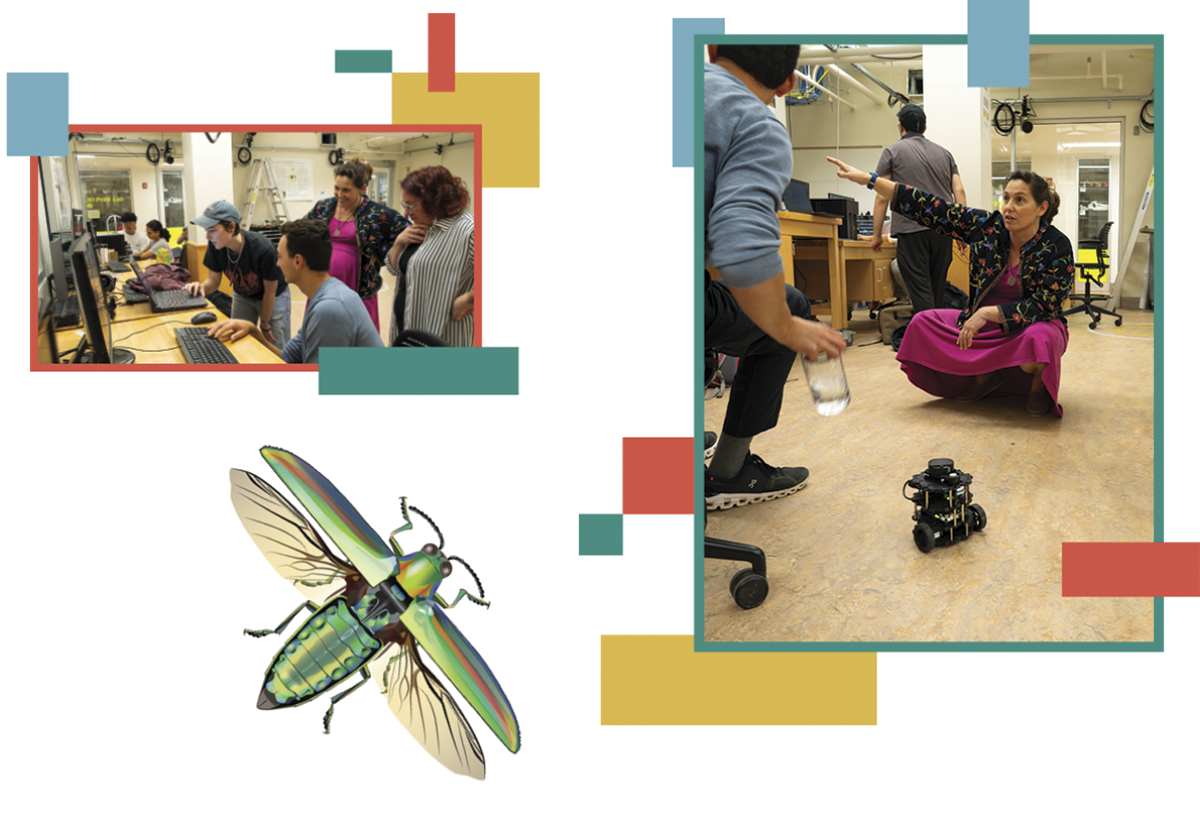

Feller (pink dress) is involved with a robotics laboratory at Union College. Her work has recently expanded into brain-machine interfaces after a student in one of her classes expressed enthusiasm for the topic—just one example of how her teaching continues to inform her research. (Image by Paul Buckowski/Union College) (Lower left) One of Feller’s digital designs. She has been hired to create logos for other labs and continues to make art as a hobby—ranging from using iridescent eye shadow to recreate beetle carapaces to shaping clay sculptures.

Feller (pink dress) is involved with a robotics laboratory at Union College. Her work has recently expanded into brain-machine interfaces after a student in one of her classes expressed enthusiasm for the topic—just one example of how her teaching continues to inform her research. (Image by Paul Buckowski/Union College) (Lower left) One of Feller’s digital designs. She has been hired to create logos for other labs and continues to make art as a hobby—ranging from using iridescent eye shadow to recreate beetle carapaces to shaping clay sculptures.

An “all-in” personality

Feller has always recognized her artistic side, but she wasn’t always encouraged to integrate it into her career plans. She was a good student, and her kindergarten teacher told her parents she would probably become a doctor. “I got that message my whole life,” Feller says.

It sunk in, and she started at HWS on the pre-med track. As an undergrad, she took an internship as a surgical assistant in a hospital. “There was a major clash with who I was as a person,” Feller says. “Literally, you are in a sterile environment. So while I was good at that job, it crushed me.”

But expectations die hard, and in her junior year, she was still looking at medical school. She decided she should do research to boost her chances. “Literally, it was just for my CV,” she says. Little did she know the experience would permanently shift her trajectory.

For this design, Feller incorporated the organisms studied in the UMBC biological sciences department for its annual, informal graduate student t-shirt.

For this design, Feller incorporated the organisms studied in the UMBC biological sciences department for its annual, informal graduate student t-shirt.

Feller did some background research and requested a meeting with HWS biology assistant professor Kristy Kenyon, who studies development of the visual system in frogs and fruit flies, to pitch an honors project. As it turned out, her pitch was a little off the mark. “It was at least within the organ system that I worked,” Kenyon says. Yet, Kenyon decided to give her a chance.

Why? “Kate Feller is such a dynamic person,” Kenyon says. “She was such an all-in, live-life-to-the-fullest kind of person, that it was very easy for me to get excited about working on a project with her despite having never had her in a class. The energy, the creativity, the curiosity—those are three words I would use to describe that initial impression of Kate.”

Research in sight

Feller and Kenyon settled on a bat vision project, and it transformed Feller’s future. Kenyon gave her a crash course in what she needed to know, and Feller thrived. The project led to Feller’s first scientific publication, reporting the discovery of a type of UV-sensitive cell in bat eyes that is evolutionarily related to the same cells in mice.

“I loved it,” Feller says. “Just the idea of thinking about how a different creature sees, because I’m so visual—it just fit so well. It took me a while to realize why I found it so exciting, but then I was like, ‘Oh, that makes sense.’”

And yet. After graduating with a double major in biology and environmental science, Feller took a position as an ophthalmology surgical assistant. She quickly soured on that, though, for the same reasons she had struggled with roles in sterile environments before. Her personal life brought her to Baltimore, and looking for new opportunities, she found Tom Cronin on a Google search.

She applied to other Ph.D. programs, but when she visited UMBC, “there was the pond, and all the grass, and meeting Tom, and I was like, ‘Oh, this is where I need to be.’”

A tight-knit group

Feller’s Ph.D. years spanned a special time in the Cronin lab. “It was an incredible group of people who formed a tight-knit community and helped each other grow into outstanding scientists,” says Megan Porter, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab during that time. Sometimes, that support involved tough love. An intervention conversation Porter had with Feller when she was experiencing a third-year slump helped get Feller’s Ph.D. back on track. The exchange helped Porter as well.

“It has helped me to be a better mentor to my students now, to have had that conversation first with a friend,” says Porter, who now is a professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “It’s an important conversation to have with any graduate student, as it isn’t the right path for everyone. There are many other careers out there for anyone who loves science.”

If Porter was the nurturing mother figure in the lab, Michael Bok, Ph.D. ’14, biological sciences, was the goofy uncle. Feller and Bok started the same year, and both needed to earn an advanced level of scuba certification to conduct fieldwork in Australia. Given the limited diving options in the mid-Atlantic, “we spent a total of 15 hours goofing around in a pretty uninspiring quarry, but it was worth it for the diving we got to do in Australia,” says Bok, who is now a researcher at Lund University in Sweden.

Feller and Bok conducted fieldwork at Lizard Island Research Station off the northeast coast of Australia for many months across five years. “Some of these stressful and intensive work experiences would probably strain some people’s friendship, but Kate and I seemed to always be quite happy with each other despite having pretty different personalities,” Bok says. “We were definitely kindred in our love for science, appreciation for being out in nature, and senses of humor.”

Feller came to love diving and did so with typical flair. “You could always tell where Kate was in the water,” Cronin says, because she always wore a brightly colored swim cap with plastic flowers stuck all over it. “It was very Kate because it made her look kind of silly but also very distinctive, because even underwater far away you could identify her.”

Dance parties and lost turtles

Alex Kingston, Ph.D. ’15, biological sciences, arrived in the lab after Porter, Bok, and Feller. “I really wouldn’t be where I am today without each of them,” she says.

Kingston, who today is an assistant professor at The University of Tulsa, was always very organized and on top of things, Cronin recalls—“very type A.” She kept the lab running smoothly as lab manager but wasn’t afraid to have fun. Feller and Kingston would have dance parties as a break from drafting scientific manuscripts. “It was hilarious when other people would come into the lab, not expecting us in the middle of the lab blaring music and dancing around,” Kingston remembers.

The group had other shared adventures, like caring for Scott, a box turtle who frequently escaped, necessitating a lab-wide search. And Feller took it as her role to decorate the lab. “In my lab today you can still see Kate stuff,” Cronin says. “She had a tendency of sticking stuff up there that didn’t want to come down again.”

Cronin’s approach to mentorship allowed each of his students to find their own way, with the level of support or independence that worked best for each of them. That means Cronin’s students have complete ownership of both their successes and their struggles and grow the confidence to face both once they leave UMBC.

“Tom was really hands off. However, he was so supportive,” Feller says. “Pretty much any time I came to him with an idea, he was like, ‘Cool, let’s do it.’ So it was that mix of, you’re steering the ship, but you don’t have to worry about resources.”

“Kate was not afraid to try anything— she was particularly inclined to do things her own way,” Cronin recalls. While she may have taken some time to find her footing, in the end, “she did really great work—really original and creative work.”

(Left) Current and former members of Tom Cronin’s research group have made it a tradition to reunite at professional conferences and take a “family photo.” From left to right: Kate Feller, Tom Cronin, Alex Kingston, Megan Porter, and Michael Bok in 2013. (Image courtesy of Tom Cronin) (Right) Feller contributed substantially to decorating Tom Cronin’s lab. One day she came home from a thrift shop with a gift for Cronin: this sketch of a cat, with the inscription, “Tom is tough. But he is your friend.” It was a perfect fit for an advisor who held high expectations along with offering generous support. It still hangs in the Cronin lab today.

(Left) Current and former members of Tom Cronin’s research group have made it a tradition to reunite at professional conferences and take a “family photo.” From left to right: Kate Feller, Tom Cronin, Alex Kingston, Megan Porter, and Michael Bok in 2013. (Image courtesy of Tom Cronin) (Right) Feller contributed substantially to decorating Tom Cronin’s lab. One day she came home from a thrift shop with a gift for Cronin: this sketch of a cat, with the inscription, “Tom is tough. But he is your friend.” It was a perfect fit for an advisor who held high expectations along with offering generous support. It still hangs in the Cronin lab today.

Rigor, excitement, and resilience

Today, Feller is focused on furthering her research, engaging her students, and raising her family—her second child arrived this October. As a faculty member, Feller is maintaining old connections and forging new ones.

“Kate is really doing a fantastic job of creating and maintaining a network across different areas of science and education, in the research that she does but also in the way that she teaches and the way she facilitates those connections across institutions,” Kenyon, her mentor from HWS, says. For example, Kenyon is now collaborating with a colleague at Union because Feller connected them. And Kenyon is using a book in her courses that features the Cronin lab’s research— including some carried out by Feller.

“What I have thoroughly enjoyed is watching Kate progress at each step along the way, and find her passion, and be able to pursue something with such rigor, and excitement and resilience,” says Kenyon.

Illuminating the unknown

Whether creating art, performing on stage or in the classroom, working hard in the lab, or collecting specimens underwater, Feller is embracing each stage of her life and career with a zest that is uniquely hers. As Cronin puts it, “She was always Kate. She never started or stopped being Kate.”

“The thing that I love most is just trying to figure out how the world works,” Feller says. “I like to describe myself as an explorer. I am not a Magellan or a person on a ship looking to explore new places—I’m pushing the boundaries of knowledge. Where is the edge, and how can I shed light on the unknown?”

Feller is on the exploration of a lifetime, discovering new things about how brains work, transforming the lives of students, and doing it all in full color. As her research program takes off, her family grows, and her network broadens, her greatest adventures may be ahead of her.