Urban development firms Future Roots and Team Elle Woods are competing to win the City of Yorktown’s Elmwood District urban redevelopment project. The teams hover over their LEGO-built cities moving black, blue, red, and orange bricks representing new parking garages, low and high-rise office buildings, retail spaces, housing, and historic buildings. The site planners, financial analysts, marketing directors, environmental and equity directors, and community liaisons are mapping out neighborhood layouts that will entice former residents to return, draw professionals, and bring businesses to the once-thriving neighborhood.

The firms’ offices are on the first floor of UMBC’s Performing Arts and Humanities Building. This is POLI 443 Urban Policy Analysis where two groups of students, seven on each team, spend six weeks developing a hypothetical urban redevelopment plan based on their understanding of urban policy, problems, and solutions. The teams then compete for the winning bid—that is, the green light of industry experts who’ve come to campus to judge their proposals.

Eric Stokan (standing) with students during the semester as they brainstorm city designs. (Image courtesy of Stokan)

Eric Stokan (standing) with students during the semester as they brainstorm city designs. (Image courtesy of Stokan)

Building a vision

“I could lecture students about the ethical, financial, structural, and environmental issues cities grapple with in the land redevelopment process, but simulations create an entirely different learning process,” says Eric Stokan, associate professor of political science. Always looking for ways to make community development concepts more engaging, Stokan worked for several years on developing an urban development class simulation.

Around this time, Ghadeer Mansour ’13, political science, senior associate at the Urban Land Institute (ULI), reached out to her former political science professor, Carolyn Forestiere seeking a faculty member who might be interested in ULI’s UrbanPlan simulation curriculum program. ULI is a nonprofit global network of professionals in every real estate development and land use sector, focusing on decarbonization and net zero, increasing housing attainability, and education. The UrbanPlan exercise requires students to design a realistic land use redevelopment plan, including a 3-D city model, that addresses private and public sector needs and wants.

(l-r) Perry Mahle, a project manager at the Whiting-Turner Contracting Company and co-chair of the Urban Plan, with Stokan and Mansour. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

(l-r) Perry Mahle, a project manager at the Whiting-Turner Contracting Company and co-chair of the Urban Plan, with Stokan and Mansour. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Forestiere suggested Stokan to Mansour. “ULI had thought of everything a student needs to understand urban development. They had a whole step-by-step manual with tabs for the history of the town, design guidelines, site plan, roles, letters from residents, a glossary of terms, and a presentation checklist,” says Stokan. He first completed a condensed version of the simulation as a participant followed by a training tailored to educators adopting the simulation into their classroom.

“The simulation gives students a critical take on how to better balance equity and economic growth, and what that means for affordable housing,” says Stokan. “They have to confront those trade-offs and understand it’s not an all-or-nothing thing. They have to be able to balance growth, equity, and environmental sustainability.”

Balancing the books

Cooperation, teamwork, and compromise are necessary for sustainable development. International student Florian Dambacher,listens intently to Alex Schultz ’25, political science, the environmental and equity director; Sam Kennedy ’26, social work, the neighborhood liaison, and Meghna Chandrasekaran ’24, political science, the site planner as he calculates the expenses. His job is to ensure the team’s ideas for creating a sustainable, economically vibrant, distinctive district stay within the city’s budget requirements and profit projections while ensuring the designs encourage cross-generational interactions that maximize the surrounding commercial, educational, and cultural resources.

Florian Dambacher (in red) with Team Elle Woods. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Florian Dambacher (in red) with Team Elle Woods. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

“It was a bit daunting at first. You have all these different requirements. You have the city that wants something from you, the investors you have to answer to who have interest groups in the community that have demands, needs, and wants,” says Dambacher. Today he is the student, but when he returns home to Technische Universität Dortmund in western Germany, Dambacher plans on using this teaching tool with his high school students. He feels this kind of simulation can be a powerful tool in any subject. “Teaching the theoretical side of a topic may be enough, but having a practical aspect has a more lasting impact on students,” says Dambacher.

Accessibility in motion

With two internships under his belt, one at the Frederick County Transit Planning Department and the other at the Maryland Transit Administration Planning Department, Travis Martin ’25, political science, was more than ready for his role as site planner. His previous experience proved indispensable as he brainstormed ideas with Aurora Quezada ’24, the neighborhood liaison, and Suhaib Mirza ’25, political science, environment and equity director.

Travis Martin (left) works on Future Roots’ redevelopment map. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Travis Martin (left) works on Future Roots’ redevelopment map. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

“A well-functioning transit system gives people the tools they need to be successful, to build a sustainable life,” says Martin, who enjoys exploring and analyzing transportation systems when he visits new cities. In the real world, he notes, there’s a lot more paperwork and sometimes years of deliberation before a development decision is made. The simulation made it possible for Travis to experience the entire proposal process. “Transportation is a social justice issue for me, not everyone is fortunate enough to have access to it.”

Defending the vision

On the day the industry professionals arrive to judge their projects, Team Elle Woods and Future Roots inspect every colorful block of their city model making sure it reflects their upcoming proposal. Stokan and Mansour are excited. This is what they have been looking forward to since they first connected. “Professor Stokan has been so welcoming and open about the whole process so that in many ways, students are leading the process themselves,” says Mansour. “Then we bring in professionals who do this planning work for their day jobs, and they mentor the students and help think through the trade-offs and issues they face as urban planners.”

Team Elle Woods presents to the hypothetical city council. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Team Elle Woods presents to the hypothetical city council. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Perry Mahle, a project manager at the Whiting-Turner Contracting Company, and Rose Dalay, operations and leasing specialist at SparkFlex, co-chairs of the UrbanPlan simulation, walk around the LEGO cities, chatting with students from both firms.

“Beyond meeting the metrics or asking the questions that the curriculum provides. I always try to ask questions to encourage students to evaluate their final decisions,” says Brennan Murray, assistant managing director of business and neighborhood development at the Baltimore Development Corporation. “Like in the real world, when industry professionals are presenting projects, you are going to get questions that call your thinking, your process, and your solutions into question. How students respond on the fly is a lesson in itself.”

(r-l) Brennan Murray (in yellow) and Perry Mahle guide students during the semester. (Image courtesy of Stokan)

(r-l) Brennan Murray (in yellow) and Perry Mahle guide students during the semester. (Image courtesy of Stokan)

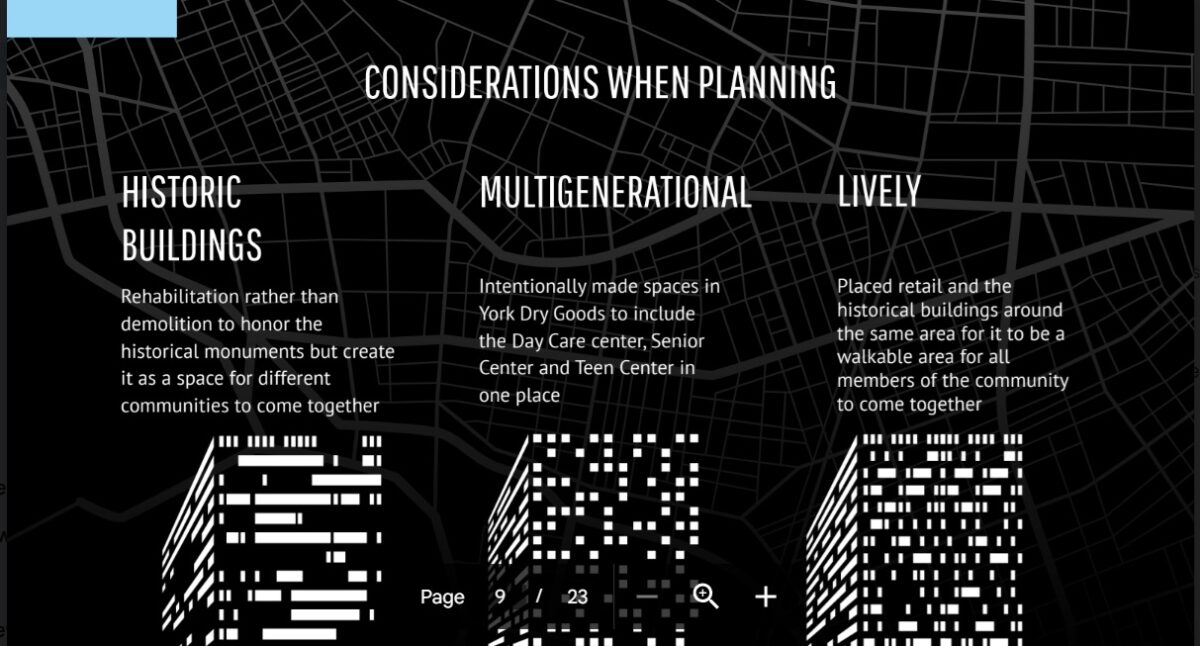

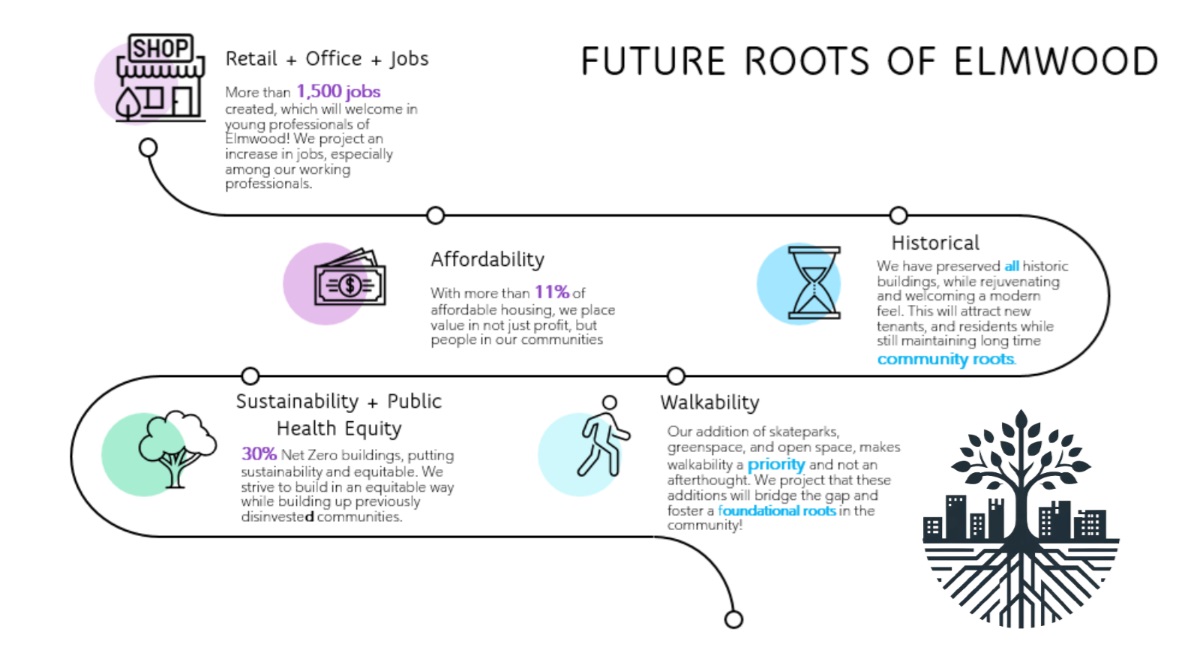

The two student firms stand before the council explaining their vision statements, site plan, and financial model. Team Elle Woods’ multimillion-dollar investment centers around multigenerational living, youth job development, and walkability.

Left: Team Elle Woods’ redevelopment plan. Right: Future Roots’ redevelopment plan.

Future Roots’ plan is geared more toward walkability, integration of essential services, historic preservation, and environmental sustainability. The council demands a clear cause and effect for each item on the financial statement. They hone in on the long-term benefits every decision would have on the area’s multigenerational community.

Team Elle Woods won the bid on many grounds, but most importantly because their finances stayed in the green. Future Roots, while presenting a compelling case, resulted in debt. Martin, the transportation planner for the team, contested the decision, but ultimately he said, “The simulation was fun and made me feel like I was doing something important.”

Role vs. real-life

As the class prepared to celebrate the end of their project, Shanika Freeman ’24, individualized studies, reflects on what she describes as an eye-opening experience that will help her in her work as a leader in Baltimore City. She is well aware of the impact real estate development can have on a city. Freeman, who grew up in Baltimore City, says the real estate design choices historically driven by segregation—favoring white communities and ostracizing Black ones—have been linked to an increase in crime, incarceration, and recidivism.

Freeman is working on dismantling such inequalities as a member of the Baltimore County Public Library’s diversity, equity, and inclusion team. So when she was given the role of marketing director, Freeman initially didn’t want it. She was weary of the role marketing has played in the negative portrayal of urban neighborhoods.

Shanika Freeman (left) with team Future Roots. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

Shanika Freeman (left) with team Future Roots. (Marlayna Demond ’11/UMBC)

“I was put off by my role because I’m more into social justice, people over profit. Marketing and finance aren’t my thing. Having to shift my focus and my personal biases was really difficult, to be honest,” says Freeman. But she didn’t give up. She leaned in. “Once I dug deep into it, I got excited about it and came to understand that without money the city can’t build; if we can’t build, we can’t help more people. It’s a collaborative effort. I learned a lot about myself as a person and also about a career path that I might take in the future.”

The Urban Plan simulation will be a standalone class in the Honors College in fall 2024 and fall 2025. For more information, contact Eric Stokan: estokan@umbc.edu.