Since 2014, multimedia artist Levester Williams has developed a personal connection and exploration with a natural material that is a historic staple of Baltimore life—Cockeysville, Maryland, marble.

Go down specific streets in neighborhoods like Highlandtown, Charles Village, Cherry Hill, or Mount Vernon and you’ll see the ubiquitous, three-to-four tiered steps made of marble outfitting the exterior of many rowhomes throughout Baltimore, much of it from Cockeysville. Beyond the steps, you’ll also find the stone in landmarks such as Baltimore’s City Hall, the Washington monuments in Baltimore and D.C., and the 108 columns of the U.S. Capitol Building.

“The stone is a literal and figurative bedrock of our nation. It’s used in many prominent monuments and institutions,” explains Williams, who is a 2023 – 2024 artist in residence in UMBC’s Exploratory Research Residency Program, a component of the university’s Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture (CADVC).

In this pilot artist residency program, Williams is collaborating with the CADVC to complete a new video art project called “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” in which the artist is researching the history of Cockeysville marble, underscoring the “intertwined history of African Americans’ plight to self-determined agency and full citizenship, and a rather benign stone.”

More than just marble

In his work, Williams examines the relationship between objects, humans, and the physical world with art that includes sculptures, installations, sound, animations, drawings, and videos. Williams is continuing that exploration in “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” part of his ongoing series focused on the dolomitic stone that is quarried in Cockeysville, 25 miles from Catonsville. The series explores Williams’ desire to examine his idea of “the beyond—where race is no longer tethered to value; where my body matters just as much as other bodies matter,” he says.

A drone image of the Texas Quarry in Cockeysville, Maryland, one of the locations where Cockeysville marble is mined. (Photo courtesy of Levester Williams)

A drone image of the Texas Quarry in Cockeysville, Maryland, one of the locations where Cockeysville marble is mined. (Photo courtesy of Levester Williams)

The artist began his exploration into the stone after reading a passage in Lindon Barrett’s book Blackness and Value: Seeing Double about jazz singer Billie Holiday’s time growing up in Baltimore. The book references Holiday’s autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, which documents her stint cleaning the marble steps in Baltimore as a teenager.

“White homeowners were obsessed with keeping the white marble stoops clean, and didn’t care how the inside of their homes looked, as long as the steps were clean,” says Williams in reference to the passage about Holiday in Blackness and Value. The steps were seen as a marker of class and economic status, he adds, explaining how “Holiday knew that and was able to bargain to get more money for cleaning the stoops.”

Through archival research, Williams learned more about the stone’s connection to Black people in Baltimore and their bodies as they handled, cleaned, and labored over the marble. As part of his CADVC residency, Williams conducted research at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, using the center’s digital archives of Baltimore’s historic Afro-American newspaper and photographer Paul Henderson’s collection of images he captured for the paper from 1930 through 1960. The archives showcase the long history of Baltimore’s Black residents who cleaned and maintained the marble steps as part of their daily routines.

“Bodies in space”

The “dreaming of a beyond” series consists of short vignettes capturing performers touching and physically engaging with structures, objects, and buildings made with Cockeysville marble at different sites throughout the northeast region. Beyond Maryland, the marble can be found in places such as the Buffalo AKG Art Museum in upstate New York; the Fisher Building in Detroit; Girard College in Philadelphia; and St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City.

In Baltimore, Williams filmed performers interacting with the (original) Washington Monument in Mount Vernon Place. Nia Hampton, an intermedia and digital arts (IMDA) graduate student at UMBC, and her mother, Sheila Gaskins, were featured in “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” filmed with the assistance of IMDA student Bao Nguyen. A sneak peek of Williams’ in-development projection demo was on display at the CADVC in February.

Video still of Nia Hampton in the vignette “Nia’s Embrace” from “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” filmed at Mount Vernon Park Place in November 2023. (Photo by Levester Williams)

Video still of Nia Hampton in the vignette “Nia’s Embrace” from “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” filmed at Mount Vernon Park Place in November 2023. (Photo by Levester Williams)

The film—which was projected onto the side of a building across from the CADVC’s outdoor amphitheater space—captures the mother-daughter duo physically engaging with the monument with movements that included hugging, caressing, scaling, and sprawling various body parts across the marble-encased statue. Williams worked with artist and intimacy coordinator Savannah Knoop to “reconfigure and think about bodies in space, non-human bodies, and what it is to give consent to these things,” he says.

“What I appreciate about Levester’s work is its level of obscurity,” says Hampton. “When I saw his work, I thought it was different—I never saw anything like it before.”

When she learned that the artist wanted the film’s subjects to be local residents with a deep connection to Baltimore’s history, Hampton referred Williams to her mother. Gaskins, a multi-disciplined artist who has been a local arts advocate and educator for more than four decades, wrote and directed “Last House Standing: A Play About the Highway to Nowhere”in 2016. The play included performers playing the role of the marbled stoop steps.

“When I was interacting with the marble [in the work with Williams], it wasn’t a pretty thing. I was thinking about my ancestors. Nia and I were having conversations about the slaves that probably built the monument. All of that was in our minds when we were interacting with the marble,” says Gaskins.

Nia Hampton (left) and Sheila Gaskins in “standing ground (On Washington)” from “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” filmed at the base of the Washington Monument in Baltimore. (Photo by Levester Williams)

Nia Hampton (left) and Sheila Gaskins in “standing ground (On Washington)” from “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore,” filmed at the base of the Washington Monument in Baltimore. (Photo by Levester Williams)

“Black folks touching the stone have been an anchor in this master-slave dynamic. I reimagined this relationship between the Black body and the stone, which is not in service of this power dynamic,” says Williams. “I’m using this stone as a way to reimagine Black folks in public spaces.”

Artistic practice as research

This fall, the CADVC gallery is set to premiere a selection of Williams’ artwork that emerges from his “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore” research as part of the introduction to the center’s public video projection gallery series, which will be on display in the Fine Arts Building Amphitheater. The series is anticipated to rotate new video artwork presentations and will run for the next several years, says Rebecca Uchill, director of the CADVC.

The fall projection presentation will also coincide with the “all matters aside” exhibition at the CADVC that will feature a retrospective of Williams’ work from the last 10 years, organized by curator Lisa Freiman. Williams’ work was previously featured in “Declaration,” the inaugural exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University that Freiman curated as the institute’s inaugural director.

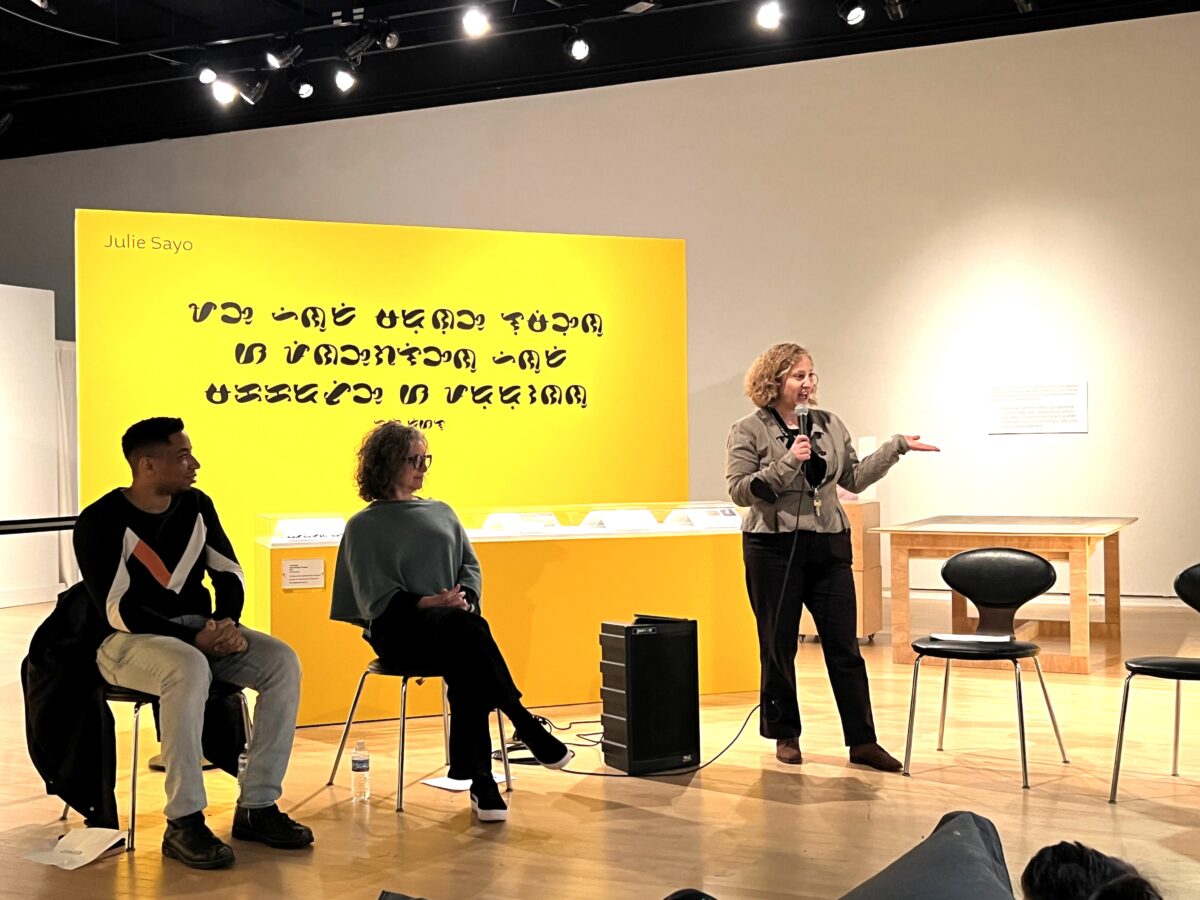

Levester Williams, Lisa Freiman, and Rebecca Uchill at the sneak peak projection demo of “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore” in February 2024 at the CADVC. (Photo by Tedd Henn, courtesy of the CADVC)

Levester Williams, Lisa Freiman, and Rebecca Uchill at the sneak peak projection demo of “dreaming of a beyond: Baltimore” in February 2024 at the CADVC. (Photo by Tedd Henn, courtesy of the CADVC)

Wiliams’ projection work will also feature an accompanying booklet that includes an essay by Michelle Wright, professor of history and Africana studies at the Community College of Baltimore County. Wright’s essay, “Scrubbed Clean,” examines the complex history of Beaver Dam marble, its use in Baltimore’s Washington Monument, and its connections to the city’s history of racial division.

Along with Williams, the CADVC Exploratory Research Residency Program also hosted artists Tomashi Jackson and Paul Rucker. Portions of the program have been funded by the Maryland State Arts Council, the Baltimore County Commission on Arts and Culture, and UMBC’s College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences’ Big Ideas initiative. The pilot program, which launched in 2022, “recognizes the inherent research that is artistic practice,” Uchill explains.

“Artists are researchers, technicians, and producers. I think some of that occasionally may be underemphasized in certain contexts, but fortunately not at UMBC. CADVC’s residency program aligns with the rigor, creativity, and civic engagement of the university at large, and feeds into other areas of our center’s programs in exhibition, publication, and creative production,” says Uchill. “This has been an especially enriching opportunity because of UMBC’s laudable, sincere belief in the importance of the arts as research.”

For Williams, the exploratory residency program is helping him to expand his interpretation of being Black and existing in public spaces: “There’s no hierarchy of us existing in space and doing that through touch is what my project is focused on. Having these performers touch the stone in any way that they want is [my idea of] pushing back and getting to that ‘beyond’.”