A blog reflection written by Women’s Center intern Bree Best

For the past several months I have been trying to conceptualize what I wanted to say about white privilege and protesting, the struggle of identifying power structures, access to privileged dissent, and a whole litany of other things that I could go on about dealing with Racism = Prejudice + Power. One recent experience sticks out in my mind as indicative of just how harmful white privilege can be in spaces that are supposed to be about social justice.

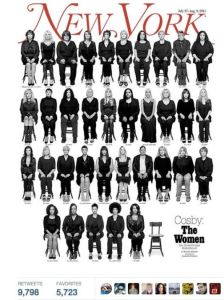

Thirty-five of the 46 women who have publicly accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault are featured on the cover of New York Magazine.

At the end of March 2015, I went to protest Bill Cosby at the Lyric in Baltimore and immediately I noticed the appalling disparity between white women to women of color. As I looked for the protest organizer to discuss my concerns, I heard the protesters shame the patrons as they were walking into the Lyric – patrons who were overwhelmingly people of color. I came to protest Bill Cosby’s rape allegations and bring awareness to sexual assault, not to further marginalize already marginalized people.

When I expressed my concerns to the white woman protest leader, her response was immediately defensive: “We’re supposed to shame the patrons. They’re the ones that paid for the tickets to come see this show. That’s how a protest works.” I tried explaining my discomfort as a woman of color seeing mostly white women protesting a black man by yelling at people of color and mentioned that many of these same people being yelled at may have experienced white people yelling at them while protesting for Civil Rights, so perhaps a different strategy would be worth considering.

Ultimately, I ended up leaving the protest after the organizer told me that I was being combative (among other unsavory things). As I drowned my intersectional feminist rage in Blue Moon and mixed drinks, I considered how much more effective the protest could have been if the white organizer and participants had used an intersectional lens to think about how systems of power influence their lives, including their approach to activism. We need more critical dialogue not just about race and racism but specifically about whiteness, which is often forgotten in these discussions because it is the invisible norm against which everything else is othered.

Disrupting this white-centric framework is crucial for engaging in anti-racism. On a national scale, the Black Lives Matter protests are a direct interruption of that a Eurocentric worldview. Just as we need to decenter whiteness in the physical spaces like these protests, we also need for “allies” to decenter whiteness mentally so that they can engage in social justice without reproducing oppressive power structures or erasing the voices of people of color.

I’ve been in many situations like the Cosby protest when a white person got defensive when I pointed out a racial disparity or racially motivated power dynamics and I tried to push them to understand how problematic that can be, at which point they would either leave or ask me to leave by insinuating that I was being “difficult to work with.” These racial interactions are an everyday occurrence for me because I and many other black people must continually navigate “white space” while also decentering whiteness. However, in order to effectively dismantle white supremacy, black people cannot be the only ones working to disrupt white space – in our communities and our minds – but rather white people must also take on the often-uncomfortable challenge of confronting their own privilege.

Most places can be considered spaces of privilege and prejudice unless they actively work against oppression.

With white spaces being virtually everywhere, my beloved Women’s Center at UMBC is no different. Throughout my internship I’ve had many conversations with Women’s Center staff about we can continue working to decenter whiteness, including more intentionally focusing on the voices and perspectives of women of color and developing strategies to more effectively enable white people to engage in constructive dialogue around race and racism. Dismantling white supremacy is a daunting task and I am equipped with the skills and opportunities to aid in this endeavor despite how exhausting this work can be.

As with most social change work, progress in anti-racist work takes time, a humbled nature, and patience. People make mistakes and call each other out. If that is the case, use the white leadership from the Cosby protest as an example of how not to react. Instead I would suggest: Take a breath, assess your privilege, welcome the lesson, and ask engaging questions that focus on creating an effective impact in communities of color. If people want to build diverse communities, then we as a community have to acknowledge and embrace our differences through understanding the greater systems at large that privileges few and oppresses many.